Apple Top 100

My fellow writer and music-lover, Connor Ferguson and I have started a collaborative project reviewing Apple Music’s Top 100 Albums. You can see our weekly posts on “The New Sincerest” Substack.

I’ll be linking the reviews here as we go through the albums.

You can subscribe to the Substack HERE.

Introduction (Written By Connor Ferguson)

On May 13th 2024, streaming service Apple Music took the audacious challenge of declaring the top 100 best albums of all time. Defined by a philosophy that was genre and era agnostic, Apple Music’s list was curated by an internal team alongside a limited array of artists (reportedly including the likes of Charli XCX, Pharrell Williams, Maggie Rogers, among others) in an editorial style, favoring opinion and artistic merit rather than hard statistical data. While countdown lists are as old as the art criticism world itself, and Apple Music’s venture on paper makes sense, the list was met with ire from the industry and everyday music listeners alike: in my personal circles, I heard passing remarks about the list's lack of genre representation (country and indie/alternative are sorely missing from the list’s upper ranks), contemporary favoritism (the newest album, SZA’s SOS, released a little over a year before the list’s publication), and demographic diversity (was this list primarily highlighting English language albums, or music that broke through to the English language market?). From Reddit to Youtube to the public forum, Apple Music was under scrutiny for its declarations.

And now, a year on, here we are at The New Sincerest continuing to question Apple Music’s 100 Best Albums list. Music criticism is inherently recursive, albums and artists and genre zeitgeists constantly requiring reassessment as public favor, sonic trends, and rising stars reframe the court of public opinion. Of course, The New Sincerest is a publication just like Apple Music’s blog (although with far less reach), so subjectivity is still the name of the game, but a year on from the list’s initial publication, we think its time to ask: are these albums worthy for a top-100-of-all-time placement?

Connor Ferguson’s Take

Favorite Track: “We Dance to the Beat”

Rating: 4.5

Worthy?: Yes

Higher or Lower?: Higher

On my personal Top 100?: Absolutely.

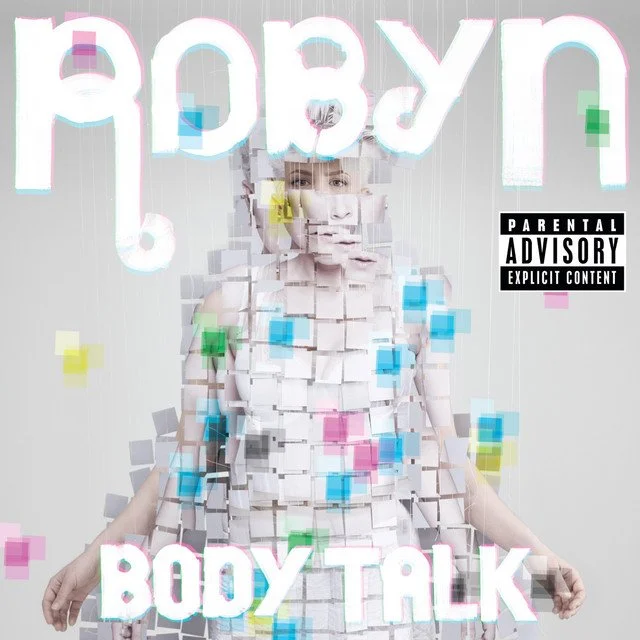

Beginning Apple Music’s countdown with Robyn’s Body Talk feels like a personal sleight against me, because this album should be much higher than #100, in my opinion. I remember reading about Robyn’s 2005 self-titled record at the peak of its blog hype, but it didn’t really click with me at the time: I was only 13 when it was released in the United States in 2007, and Robyn’s cooler-than-you persona felt a bit icy to me. In August 2010 though, freshly heartbroken from pining for someone for two years after just coming out of the closet, I saw Robyn perform “Dancing on My Own” at the MTV Video Music Awards, and while Lady Gaga took home basically every major award that night, what I remembered most of that event was Robyn’s spare, emotive singing and dancing. Once I got a laptop for Christmas that year, and was able to burn all my own CDs, she quickly took the top spot in my car stereo’s rotation, bad dates and hard days at work and long nights spent studying and applying for colleges and scholarships soundtracked by her pop savvy. I became a complete and total Robyn acolyte. This reverence, of course, is thanks to Body Talk, Robyn’s masterpiece, an album jam-packed with reflection, invention, homage, humor, and most importantly of all, vulnerability.

A decade and a half past its release, it could be easy to look back at Body Talk and see it as somehow quaint: in an era of Lady Gagas and Beyonces and Keshas and Katy Perrys, who were all building larger-than-life concept albums and arena tours, Robyn’s approach to pop music (while no less bombastic) feels less pretentious, more homegrown, even with all the bells and whistles of the ‘80s throwbacks and dance trends she pulled into the aesthetic of Body Talk. The four-on-the-floor beats, the skyscrapping synths, the shout along choruses, these sounds are all threaded through the album’s fifteen tracks, sounds that were topping the charts and blowing out the speakers at clubs at the time. But Robyn’s wizened perspective on relationships, on the cannibalization of the star machine, on the cartoonishness of pop braggadocio, gives Body Talk a paradoxical softness and edge that compliments the bubbling production and lovesick tones of the whole project.

A few tracks come to mind here: “Fembot”, one of the most outrageous tracks, paints Robyn herself as a ready-to-please partner (“Initiating slut mode; all space cadets on deck”) but lays down the law just as quickly with a wink (“There's a calculator in my pocket, got you all in check”); the propulsive “Love Kills” has some fantastic takedowns of a jaded lover (“Stolkholm Syndrome in misery / there’s a penalty for love crimes”) but is more centrally guided by her warning her audience to protect one’s heart; and the teasing “Hang With Me”, one of Body Talk’s most dizzying tracks, sees Robyn friendzoning a suitor with her words, even though the percolating instrumentation reveals that her guard is certainly breaking.

Even when Robyn decides to lean more heavily into one side of the formula, the results are still noteworthy: on the rap-battle-esque “U Should Know Better”, Robyn responds to Snoop Dogg’s fairly cliche and expected sexual and drug conquests (though he’s in top form here) by establishing herself as the true knockout in the room, someone who is ready to throw down with the Vatican to abolish celibacy and institute a black Pope, stake her claim as a pop revolutionary in the music industry and its propensity to discard aging female artists, and comes to blows with the literal Prince of Darkness himself—and comes out victorious. Of course, pure and unadulterated sincerity balances the scales on Body Talk’s first single and opening track, “Dancing On My Own”, a perfect mission statement for the record, but I won’t dig too much into that one: it’s readily apparent that it’s one of the best and most important pop songs of the 21st century so far.

Instead, I’d like to focus on two facets of Body Talk that became more clear to me on this latest listen. First, I have to admit that, despite my adoration and personal connection to Body Talk, the album is not perfect. Filler as a concept is part of the history of pop music, especially in the industry’s favoring of singles over albums in the contemporary market, but a couple of tracks simply don’t shine as much as the others here. Most egregiously, the closer “Stars 4-Ever”, while pleasing, is peak 2010s affirmation pop, and it has not aged nearly as gracefully as the project as a whole; it’s a bit mind-boggling that it's included here when a handful of other tracks from the album’s innovative three-EP release strategy (“Cry When You Get Older”, “Criminal Intent”) would have made much more of an impression.

Second, however, is the realization that Body Talk still has new layers to uncover with repeated listens, especially now that I am closer in age to Robyn herself when she released this project. In particular, the album’s subtly political perspectives, showcased on deep cut “We Dance To The Beat”, have only gained more relevance since 2010: across its dense lyricism and robotic vocals, Robyn lists personal and political cataclysms as warnings (“false math and unrecognized genius”; “bad kissers clicking teeth”; “your brain not evolving fast enough”; “another recycled rebellion”; “radioactivity blocking the exits”), always framed by the introduction of “we dance to the beat”. In other hands, this could be a nihilist manifesto, an admission that 21st century life is, honestly, pretty terrible. But, of course, Robyn softens the blow with a final verse that reclaims joy (“a billion charges of endorphins”; “love lost and then won back”; “gravity giving us a break”) and a killer bridge breakdown where the song’s key line is chanted: “And we don’t stop!”

For Robyn, pop music is rallying call and protest, balm and medicine, affirmation and accountability, and an important tool by which to situate herself within the world through a catchy chorus and a bumping synthesizer. For her fans, like myself, her music fulfills the same roles, a pop lodestar who always has the right word of wisdom for a heartbreak or a triumph. We dance to the beat, and we don’t stop.

Wenger’s Take

Favorite Track: “Hang With Me”

Rating: 4

Worthy? Yes

Higher or Lower?: Stay where it is

On my personal Top 100?: Yes

It’s 2011, a year after the release of Robyn’s Body Talk. I’m fourteen at my aunt’s house with a bunch of my girl cousins. We’re watching Youtube on her TV, learning how to be girls from music videos and vloggers. Someone puts on a cover of “Call Your Girlfriend” by Robyn. The video is shot in someone’s kitchen — three young women doing an a cappella rendition with their hands clapping out a rhythm on the table and singing in haunting harmony. A twenty-tens black-and-white filter over the home video gives it the quality I must have thought of as “artsy” back then.

This Erato cover was my first encounter with Robyn. When you come to a song through a cover, your future listening is tempered by your original listening. Most often, I like whatever version of the song I come by first, and this is a bias that is hard to overcome. But not the case with Robyn. Later, when I heard the original “Call Your Girlfriend” I was aching with the exact teenage love pains that Robyn makes music to heal. It's longing and desire packaged in bright electronic sound. The danceable beat clashes against the desperation in the lyrics.

Robyn’s Body Talk is an album for dancing out of your girlhood and into a new, shimmering skin. It’s an album that presents femme braggadocio and unstoppable rhythm as an antidote to evolving heartache.

Some people say every book of poetry has a poem in it that will tell you how to read that book. If there is a song on this album that acts as its manifesto, it’s surely track #9: “None of Dem.” In it, we see Robyn step into her reign over the club.

“None of these boys can dance/Not a single one of them stand a chance,” Robyn sings in those opening lines. “None of them get my sex/None of them move my intellect.” Listening, you can almost see her strutting into a club, looking around at the badly dancing boys and groveling club goers as they turn to take her in.

Robyn really launches into her plans for the future of music when she sings: “Play some kind of new sound/Something true and sincere…/None of these beats are raw/None of these beats ever break the law/None of them kicks go boom/None of them bass lines fill the room.” It’s like a campaign speech. Robyn presents herself as a new and rightful ruler, taking over the dance scene. She’s got beats. She is the law. She’s going to play a new sound. Something true and sincere.

And, my God, Robyn’s kicks really do go boom. I didn’t stop dancing to this album all week. I played it while I walked my dog, while I packed my apartment for a move, while I drove Door Dash deliveries, bumping my shoulders to “Dancehall Queen” and “Don’t Fucking Tell Me What to Do,” as I picked up orders. No one can contest Robyn’s sheer bop-producing power.

But it’s this last part of the manifesto that gives me pause: the idea of sincerity.

Not long before Connor and I started this project, we listened to Lorde’s album Virgin, an album with some lyrics that make you cringe at the rawness of teenage angst expressed in cliche. But, Connor made the good point that, in some ways, it’s this simplicity of lyrics — this near-cringe state of honest emotion — that makes the album succeed.

As with Virgin, there are some lyrics in Body Talk that feel more like a teen girl’s diary scrawl than delicate poeticism. Metaphor is abandoned for tired truisms and cheap rhymes. In “Love Kills” Robyn sings: “Protect yourself, 'cause you'll wreck yourself/In this cold, hard world, so check yourself.” And in Time Machine: “Hey, what did I do?/ Can't believe the fit I just threw/Stupid, (hey) wanted the reaction.” And in “Stars 4-Ever”: “You and I, shining lights are what we are/Look at the sky and I am never far”

But this is pop music, not Shakespeare. There is an amount of silliness and sentimentality that we allow from our pop stars. Moreover, as I read my own critiques, comparing the lyrics to a teen girl's diary, I can feel the implicit sexism.

(I am thinking as I write this of the opening lines from the by-now cult-classic Jennifer’s Body (2009): “Hell is a teenage girl.” The phrase comes to mind any time I think about girlhood.) What is it that makes people cringe at raw emotion? And why do we so readily associate it with teenage angst and feminine hysterics?

Perhaps it is easy to critique some of the lyrical shallowness in Body Talk because it communicates an uncomfortable depth of feeling — the kind of feeling we only know how to associate with youth (girlhood especially) when the hurts of heartbreak hit harder.

Besides, maybe when we cringe, we are really cringing at ourselves. Because isn't there something embarrassing about wanting to be with someone (“Stars 4-Ever”)? Especially when they don't want you back (“Dancing On My Own”)? Or if they are already with someone else (“Call Your Girlfriend”)? Maybe we cringe at the rawness of emotion because what we really feel is shame at our own empathy for that exact rawness. We are all dancing in the corner, watching someone we love kiss someone else.

I recall now an essay by Leslie Jamison, “In Defense of Saccharin(e)”:

“When we criticize sentimentality, perhaps part of what we fear is the possibility that it allows us to usurp the texts we read, insert ourselves and our emotional needs too aggressively into their narratives, clog their situations and their syntax with our tears. Which brings us back to the danger that we’re mainly crying for ourselves, or at least to feel ourselves cry.”

Despite the cheesiness of some of the lyrics, this album is nonstop good. Robyn knows how to undercut the vulnerability with the kind of electronic landscape that lets the sentimental feelings rise and fade into the background, like smoke hovering above a crowded dance floor.

Robyn’s more mature album may be 2018’s Honey. But while the sound is more developed, Honey is lacking some of the raw sincerity that is the blood pumping through Body Talk. It is strange that the exact songs on Body Talk that make me cringe, are also the ones I love the most because they make me remember what it was like to be a teen and what it is always like to feel that tired cliche of an emotion that is desire.

#99 Hotel California By The Eagles

Wenger’s Take

Favorite Track: “New Kid in Town”

Rating: 3.6

Worthy?: No

Higher or Lower?: N/A

On my personal Top 100?: No

Replacement pick: Boston - Boston (1976 - it’s just more fun!)

Hotel California is an album so famous, its cultural impact so pervasive, that it almost feels pointless to write about again. So much ink has been spilled and critical energy spent on this album that writing about it both an intimidating and redundant task. But we’re coming up on Hotel California’s 50th anniversary, so it feels as good a time as any to do just that — so write I will.

The Eagle’s 1976 album ranks at #99 on Apple’s Top 100 Albums. That’s about as near-bottom as bottom gets, but it made the cut where some other 70’s bands did not (The Who isn’t on the list, nor are Jethro Tull, YES, Grateful Dead, Rush, or Queen). So what is it that makes this album worthy of such serious canonization? And does it stand the test of time?

Before I get further, I figure I should use this opportunity to ask what makes an album deserving of a place on, to use Apple Music’s phrase, a “definitive list of the greatest albums ever made.” How does one even decide what goes on such a list?

While I can’t pretend to have been privy to the discussions had in the creation of Apple’s Top 100, there are a couple of factors that go into making an album a classic. Some of the factors include broad appeal, critical reception, cultural impact, and artistic merit. Considering this, I’ve decided to make a little list of DSM-style diagnostic criteria that might be used to determine the “best albums” of all time. Here it goes.

To be diagnosed as the greatest album of all time, an album must display at least 4 of the following symptoms.

✅ The album has changed the genre or music in a fundamental way: Did the album contribute something new? Did it do something bold or daring that future artists cite as deeply influential? What is the album’s musical impact?

✅ The album represents a time period or idea and transcends itself as a musical object, reaching the level of cultural artifact: I’m talking like, this album is something UNESCO would put on their list of intangible cultural heritage items. It defines a generation, captures a moment, or expresses a societal mood so perfectly as to become the definitive shorthand for that generation/moment/mood.

✅ The album must have reached best-selling status: This is simply a way to gauge broad appeal and general popularity.

✅ The album has been nominated and/or won a few major awards: This is an imperfect, but decent way of judging the critical reception of music. It might also be worth looking into what reviewers were saying about the album upon its release.

✅ The album is full of bangers all the way through, or most of the way through: The album’s tracks create a no-skip, or nearly-no-skip list of nonstop goodness.

Listen, I know it's an imperfect list, but it’s hard to be perfectly analytical about art, right?

So, let’s run Hotel California through this list.

✅ The album has changed the genre or music in a fundamental way: I would say yes. The blend of country and rock, the mythologizing of California, the harmonies over astounding guitar riffs — they are bringing something fresh to the genre. They updated the ‘60s California sound and brought it into the next decade.

✅ The album represents a time period or idea and transcends itself as a musical object, reaching the level of cultural artifact: Yes. The album is, to use Apple Music’s phrase, “a snapshot of ‘70s excess and the soundtrack to the comedown.” The title track has come to mean many things to many people. It’s a song that has become more than just its music.

✅ The album must have reached best-selling status: Unequivecollay yes.

✅ The album has been nominated and/or won a few major awards: Hotel California won the Grammy for Record of the Year. They were nominated for album of the year, but lost to Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours.

⭕️ The album is full of bangers all the way through, or most of the way through: I can’t say it is.

So the album passes with flying colors. Then why is it I still don’t think it’s on the list of “best” for me? Well, to be frank, aside from its starting three tracks, the album is… kind of boring.

But that’s a little mean. Let me be a bit more specific. The three songs that kick off the album are good. Really good. They’ve endured both lyrically and musically. The title track is still just unbelievably awesome. The lyrics are sort of endlessly interpretable in the way you want a good poem to be, and the composition creates an incredibly immersive environment. “New Kid In Town,” has the traces of country that I love, and Don Henley’s smooth vocals swim well through the quiet sadness of the song. And then there’s “Life in The Fast Lane,” with those amazing opening lines “He was a hard-headed man, he was brutally handsome/And she was terminally pretty” — talk about a to-the-point characterization. The storytelling in that song is fun and devastating. It’s a love-story gone wrong and the American Dream corrupted. It’s Rock and Roll cruising high and falling hard.

But after that, the album plunges into some frankly mediocre tracks. They’re fine songs, but they aren’t “GREATEST ALBUM OF ALL TIME” songs. You’ve got “Pretty Maids All In A Row” and “Try and Love Again” which are a bit slow. I like the latter better than the former, but even then, they aren’t saying anything particularly new or interesting. Then there is “Victim of Love,” which has a decently fun chorus, but fails to impress otherwise.

And I will admit, I did find something to like in “Wasted Time” and “Wasted Time (reprise)”, but not because they were ‘good’ songs, but because of the theatrical use of strings and the dramatics of the singing. I loved them exactly because they are sappy in a way that feels so ‘70s. At the same time, I just kind of roll my eyes when we get to the last lines: “Maybe some day we will find/That it wasn’t really wasted time.”

The track I had the most trouble with was “The Last Resort.” It isn’t just the sentimental piano that starts the song, there is something a bit didactic about the lyrics, even though there are some good lines throughout. It’s one of the song’s Don Henley is most proud of, and yet its environmentalism gets near-preachy even for me.

Granted, writing a political song is hard. People often come to music to escape politics, not to have moralistic screeds sung over chords playing through their headphones. This isn’t to say music can’t or shouldn’t be political, but that the music has to be its own art and not just a vehicle for an ideological speech. If the music doesn’t stand on its own, the result is something closer to propaganda than art.

And OK, this isn’t the worst environmental song I’ve heard (that would probably be “Wake Up America” by Miley Cyrus, but even then her youthful idealism excuses her uncomplicated approach to the issue).

Even with the more on-the-nose lines of “The Last Resort” (“some rich men came and raped the land/no body caught them” and “‘Cause there’s no more new frontier/We have got to make it here”), I do like the symmetry of the album. “Hotel California” and its dark excitement kick us off, and we end with “The Last Resort,” and its mournful view of a dying paradise. That’s smart structure for an album. But it’s the middle region of Hotel California that just doesn’t work for me.

Perhaps that’s the question at the end of the day: can a highly-praised, best-selling, and culturally impactful album like Hotel California still count as a “best album of all time” if you just don’t like most of it? The answer for me, was, sadly, no.

Connor Ferguson’s Take

Favorite Track: “New Kid in Town”

Rating: 3.5

Worthy?: No

Higher or Lower?: N/A

On my personal Top 100?: No

Replacement pick: The Roches - The Roches (1979 - more nuanced and timeless storytelling)

Two albums in, and my opinions are probably going to start upsetting readers already (and to reference another music critic, “Y’all know this is just my opinion, right?”). The Eagles are a beloved band for a reason, and I want to start this assessment by describing some of the reasons why they are so beloved: their sun-drenched guitar lines which beautifully evoke summer heat and a certain dehydrated malaise; their truly heavenly harmonies, which elevate their vocal leads to something more sophisticated than many of their other peers at the time; their ambitious lyricism and storytelling, which through the mists of time and many karaoke fails has probably been a bit obscured. There’s a reason “Hotel California”, the title track of Hotel California by The Eagles, is a song that has persisted throughout the half century since its release: each of the elements of the Eagles work I respect can be found in this song, something for each type of listener to latch onto. “Hotel California” is a monolithic achievement, a song that is so thoroughly and compelling integrated into the pop culture mythology of America that it’s almost blinding in its impact. Hotel California, as an album though, is not a monolithic achievement.

But why? Why does this album, which is so important to so many people I know, which is spoken about in so many publications and lists similar to Apple Music’s 100 Best Albums, which has influenced plenty of bands who followed The Eagles that I enjoy, not work for me? Well, it’s complicated, so let’s try to break it down in a few different ways.

First (and, surprisingly, the least interesting to me as a listener), Hotel California is so frontloaded that it makes sense why the album leaves such a strong impression. The opening salvo of “Hotel California”, “New Kid in Town”, and “Life in the Fast Lane” is an all-time great run of rock songs from this era: sweltering, sprawling, and also just a lot of fun, these three tracks perfectly capture what The Eagles were going for sonically on this record. They also articulate fairly well what The Eagles and, particularly, frontman Don Henley were trying to say about the state (and state of mind) of California at the time of its release; in a retrospective interview with Rolling Stone, Don Henley said:

They're the same themes that run through all of our work: loss of innocence, the cost of naiveté, the perils of fame, of excess; exploration of the dark underbelly of the American dream, idealism realized and idealism thwarted, illusion versus reality, the difficulties of balancing loving relationships and work, trying to square the conflicting relationship between business and art; the corruption in politics, the fading away of the Sixties dream of “peace, love and understanding.”

From the apocalyptic vision of the album’s titular establishment, to the drifting soundscape of the drifting protagonist in “New Kid in Town”, to the electric guitar licks and anthemic chorus of “Life in the Fast Lane”, Don Henley and co. feel perfectly calibrated, firing on all cylinders in their rock ‘n’ roll machine, all sticky choruses and a freewheeling attitude that has a bite to its seemingly carefree nature. Yet that momentum eventually gives way to a middling middle stretch, right when the album should be reaching its peak: “Wasted Time” has a nice build, with an orchestral swell near its end that aims for the heartstrings, but it simply doesn’t punch at the same weight as what proceeded it, and “Victim of Love” to “Try and Love Again” regrettably commits a cardinal sin of rock and pop music: these songs are simply just quite forgettable, power ballads and grand enmeshments of guitar and piano executed much better by the likes of their peers (Fleetwood Mac, but… more on them much later on in this list).

Second, however, comes down to its lyrical content, and specifically the way The Eagles aim to critique the dissolution of the American Dream through a couple key techniques, most prominently their representation of women in their music. In each of Hotel California’s songs, there is either a heroine or a femme fatale or a naive young woman at their center: sometimes they are the object of affection, sometimes they are a temptress, sometimes they are a symbolic representation of a hope or optimism that will ultimately become dashed. The Eagles themselves have made this focus on women characters explicit in interviews as well, such as when they told the Daily Mail in 2007:

Some of the wilder interpretations of that song have been amazing. It was really about the excesses of American culture and certain girls we knew. But it was also about the uneasy balance between art and commerce.

American excess and “certain girls” are continually juxtaposed together not only in their interviews, but also in their storytelling. And while I don’t mean to imply in this analysis that male writers cannot possibly write from the perspective of women (as a creative writer myself I certainly hope that is not true), there is something distinctly paternal, and, occasionally, a bit misogynistic about the representation of women in these songs. Women in Hotel California are chaperones into metaphorical hell (“Hotel California”), troublemakers who always need a little more and seem to lead their men into disaster (“Life in the Fast Lane”), or worst of all, manipulators who ask for the difficult situations they are in (“Victim of Love”). The paternal spin lives alongside these more dated representations of women through the male gaze, creating a strange narrative dissonance where women are either meant to be saved or condescended to in their comeuppance. Take the initial verses of closing track “The Last Resort”:

“She came from Providence

One in Rhode Island

Where the old world shadows hang

Heavy in the air

She packed her hopes and dreams

Like a refugee

Just as her father came

Across the sea

She heard about a place

People were smiling

They spoke about the red man's ways

And how they loved the land

And they came from everywhere

To the Great Divide

Seeking a place to stand

Or a place to hide”

As the narrative of “The Last Resort” progresses, and The Eagles more directly and critically assess the United States claiming of land out west and the eventual creation of the state of California, it becomes clear that this female protagonist is not really a woman at all, but rather a symbol by which The Eagles can critique the American Dream and its need for growth, for expansion, for discovery, and the many costs that come with that search. This doesn’t necessarily have to be a bad thing (and “The Last resort” does draw attention to the dangers of colonization and occupying of indigenous land in its critique as well, so there’s value here), but when arriving at this closing track, after the rest of Hotel California has framed women in a particular lens, it leaves a bad taste in my mouth as a listener. I really just don’t think some of these representations have aged well, and while some of that curdling can be blamed on the time of the album’s release, it doesn’t take too much looking to see other artists who were analyzing and critiquing the American Dream through the representation of women in much more nuanced and compelling ways. The Roches’ funny, wise, and moving self-titled debut record, a gem of 1970s soft rock/folk rock, perfectly executes this type of narrative in “Hammond Song” while also providing space for the female protagonist in question to speak for herself.

Third, in the long shadow of the 1960s’ counter cultural movement and free-love attitude, it makes sense that The Eagles would perhaps be skeptical of a certain Manifest Destiny ideology that drove the United States to its condition at the celebration of its bicentennial, the postwar boom after World War II long gone and the Vietnam War having just ended a year prior to its release, an uncertainty about the future of America looming as the 1980s approached. But in recent years, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the integration of generative AI into almost every software program and phone operating system and education platform, and the second election of Donald Trump into the Presidential Office, I’ve been thinking about how fine of a line separates liberal critiques and conservative critiques of the American Dream: reactions to excess, to accessibility, to certain liberties for certain groups, to demands for change, often have the same origin or source, even if the critiques are then filtered through specific political affiliations. In their prime, and specifically during the Hotel California-era of their career, The Eagles perspectives on the American Dream probably read as quite revolutionary or well-spoken, but through a 2025 lens, I’m not sure how well their commentary holds up when their grievances with America are illustrated by unkind representations of women.

Interestingly enough, everything The Eagles have to say is articulated with more empathy and nuance in a piece of art from 1975, a year prior to Hotel California’s release: Robert Altman’s film Nashville.

I watched Nashville after listening to Hotel California, after I’d begun to question its political and social commentary and had been doubting myself, wondering if I was being too critical, too harsh on a piece of media from a specific time and place. Nashville, though, demonstrated to me that art from that era can stand the test of time (part of that may be thanks to the fact that Altman’s main collaborator on the film, scriptwriter Joan Tewkewsky, is a woman, and that he allowed each member of his cast to add depth to their characters with improvised dialogue), and that it may actually have more to say about our contemporary moment than even its moment of origin. Taking place in the capital of country music (and using that city in a similar way to how The Eagles use California), the film has aged so incredibly (somewhat unfortunately, but mostly beautifully) that it manages to speak poignantly, critically, and honestly to our contemporary cultural and political moment 50 years on from its release. Truly a modern American epic, it’s a pointed look at the intersections of country music and the way it speaks to and for a specific demographic of middle class families and aspiring artists; the evolving yet confusing ‘70s, at America’s bicentennial as it aged into a rebellious adolescent state of itself; the way men project their desires and angers and grief onto the world and, frequently, the women around them, including Barbara Jean, the tragic figure at the center of the film played by Ronee Blakley; and the complicated yet recursive ways cultural figures are martyred (either literally or metaphorically) in response to or as a catalyst for shifting moral perspectives on the history and future of America. Despite all these knotted thematics and philosophical critiques, Nashville also manages to be a fantastic hang-out movie, orbiting around 20+ characters as they weave in and out of each others’ lives in public and private spaces, negotiate their shifting and troubled senses of identity, and attempt to take care of their community despite the impulse to serve one’s own interests. How often do our selfish feelings win out? The film remains ambivalent about this.

Ultimately, Hotel California remains, to me, a product of its time, a phrase that is a double edged sword. On one edge, The Eagles captured a snapshot of a time in the United States filled with uncertainty, communicated through impressive musicianship and enough genre refinements to basically define the “dad rock” genre as we now currently know it; on the other edge, in its attempts to reveal the dark underbelly of the American Dream, with fifty years of hindsight, it simultaneously reveals a dark underbelly to the band and the state of rock music in the 1970s in general, when men believed they could save the country (or at least speak truth to some sort of distorted power) without reflectively considering how they themselves fed into the destructive and corrupted cultural narratives of the time.