The early 1970s were big for environmentalism. April 22nd of that year saw the inaugural Earth Day, an event that took the nation by a storm with marches and actions across the country — nothing like the skeleton of activism that Earth Day represents now. 1970 was also the year Nixon created the EPA and Congress approved amendments to the Clean Air Act. 1972 brought the Clean Water Act and 1973, the Endangered Species Act. Joni Mitchell released “Big Yellow Taxi” in 1970, singing about the paving of paradise and the dangers of DDT. The next year, Marvin Gaye gave the world “Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)” and Douglas Trumbull’s sci-fi film Silent Running hit theatres.

Trumbull was a genius of special effects, having helped Stanley Kubrick with 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and later Steven Spielberg with Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977). Though Silent Running didn’t kill at the box office, its environmental themes and vision of a future society divorced of plant life has led to its lasting appeal.

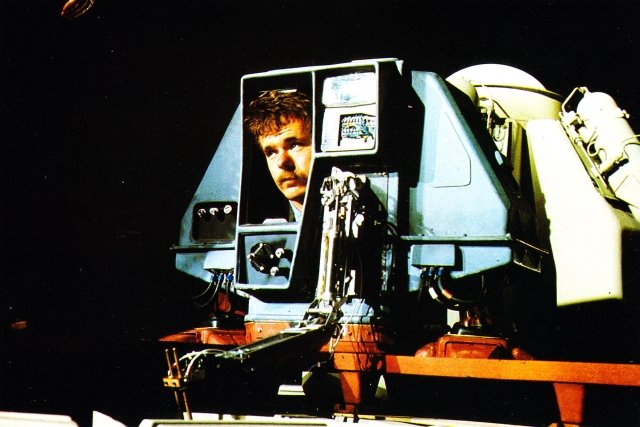

My dad showed me Silent Running years ago. It’s on his list of movies that should be remade. To be fair, after a rewatch, Trumbull’s special effects hold up surprisingly well. Trumbull built a 25-foot model for the spaceship exteriors and filmed the interiors aboard an aircraft carrier. The ‘drones’ are played by bilateral amputees in robot outfits. It’s clear why Trumbull had a reputation as a special effects guru.

So if the film isn’t dying for new computer animation, why remake it? Simple, because like any good sci-fi, this film is more than a thought experiment—it is a prescient warning.

Set aboard an American Airlines—yes, that American Airlines—spacecraft, the narrative follows Freeman Lowell (played by Bruce Dern) and his three crewmates as they tend to the last of the world’s forests. The forests are contained in huge geodesic domes attached to the main craft. Each dome contains a different ecosystem. The last of the earth’s plant life has been launched, as Lowell says, ‘millions of miles’ into space.

The plot really kicks off when Lowell and his crewmates are informed they are to discard the domes, use nuclear explosives to destroy the forests, and head home.

What we don’t see in this film is this ‘home’ — Earth itself. All we know of it is what Lowell and his crewmates provide through dialogue. “On Earth, everywhere you go the temperature is 75 degrees,” Lowell says. “Everything is the same. All the people are exactly the same. Now what kind of life is that?”

Lowell’s dread of this homogeneity is countered by his crewmate who defends Earth as a place where “There’s hardly any more disease. There’s no more poverty. Nobody’s out of a job.”

This conversation is where the film’s main defense of forests is laid out. Lowell returns: “You know what else there's no more of my friend. There’s no more beauty and there’s no more imagination. And there are no more frontiers left to conquer. And you know why? There’s only one reason why…and that is nobody cares.”

This is what most confounds and interests me in Silent Running. At its core it is an environmental film that advocates the preservation of forests, not to prevent climate change or ecological degradation, but because the beauty of forests is in and of itself valuable.

If the world is as they describe it a solid 75 degrees with no hunger and no poverty, its hard to imagine it as a dystopic. In fact, it almost sounds like a paradise. (Especially for the modern viewer, who sees temperature rises and water shortages as a real impending danger.)

But Lowell does not view the climate-controlled, abundant world below as a boon. As his crewmates begin to launch the domes into space and detonate them, Lowell takes action. He blocks the entrance to one forest, fights, and eventually strangles one crewmate. He launches the other two out to space and detonates them along with the forest. Eventually, he is alone on the ship with three maintenance drones and one forest.

Lowell commits murder to preserve beauty. The justification of his actions is blurrier even than some modern environmental terrorists who explain their violence in terms of saving lives—those of animals and plants and of future human generations. The sin of Lowell’s victims is that they don’t see the value in nature, whereas the sin of oil executives is that they actively cause damage.

But beyond beauty, Lowell’s other defense of nature is more intriguing: If we destroy nature, Lowell says, there will be “no more frontiers left to conquer.” This language of conquest is out of place in the mouth of the tree-hugging hero. Yet when the earth is tamed, climate-controlled, and utopian, what else does nature represent, but what man perceives it as. In Lowell’s case: a space of nature, imagination, and wilderness to be conquered.

In his article “The Ends of the Earth: Nature, Narrative, and Identity in Dystopian Film,” Rowland Hughes writes that Lowell’s “remark that there are ‘no frontiers left to conquer’ suggests the extent to which nature represents to Lowell a crucible for forging human identity.”

Silent Running’s environmentalism is one based in a somewhat anthropocentric view of nature. It provides beauty for mankind, but it also provides struggle. The struggle then, is perhaps what Lowell misses in the futuristic earth. There is no wilderness to struggle against when food is made of synthetic materials and spat out by a machine. There is no heat or cold to fear when the climate is always a cozy 75 degrees.

The ship represents a space where this dichotomy is played out. The domes are a wilderness of beauty and labor while the craft itself is a place of fun and relaxation (with a rec room for poker and futuristic billiards, go-cart-like vehicles to ride, and a kitchen that cooks for you).

It is shocking then that after he successfully offs his crewmates and makes away with his precious forest, Lowell spends much of the second half of the film in the ship proper, spending his days playing poker with the drones and ignoring the trees until one day, he finds them dying from lack of sunlight.

Does the film then argue that even the most fanatical environmentalist opts for the comforts of technology in the end? That the modern tree-hugger would rather game with the robots than sing with the birds?

Further, as Hughes argues in his article, the ‘nature’ depicted in Silent Running is far from the harsh wilderness of earth where an unskilled hiker is subject to hunger, thirst, and the raging elements. Lowell’s beloved forests are in reality not wild at all, but subject to the whims of the men who built the ship and the robots who help tend the gardens. “Silent Running depicts a ‘nature’ that has already been reduced to a park or a garden,” Hughes writes, “it is entirely circumscribed by, and dependent upon, human technology.”

Hughes couldn’t be more on the nose. Trumbull based his geodesic domes on the Missouri Botanical Garden’s Climatron Dome. So what Lowell hopes to preserve is more of a glorified botanical garden than a forest.

The film ends with Lowell setting the trees up with electric lights, launching the dome into space with a drone to care for them, and blowing up the ship with him on it. The last remaining trees are left floating in the infinite stars. The last person who cares about them is gone himself.

*

Final Thoughts:

There are of course other aspects of Silent Running that may give the inquiring viewer pause. For one, who is funding this conservation project? The crafts are property of American Airlines, and everyone on them seems to be American. Does this mean that the utopian earth below is a globalized and Americanized world run by large corporations?

All questions of the deforested but plentiful earth are left unanswered. I wouldn’t mind a little more elucidation on that topic if the film is ever remade.

Trumbull died in February of 2022. In 2010, he made a short video in response to the BP Oil Spill that shows and concept for a method to stop the leak.

If you have any interest in learning more about the film, you can see a documentary about its making here.